Tailbone pain in the doctors practise

This page is created especialy for physicians and GP’s. Based on a case study it will be claryfied what the characteristics are of coccydynia, how diagnostics works and what the referral options for treatment are.

Key Messages

- Coccydynia is frequently associated with significant pain and functional limitations and is often under- or misdiagnosed in healthcare.

- In most cases, the diagnosis can be established clinically; routine imaging usually provides little added value.

- Treatment is commonly focused on pain relief, with outcomes that are variable and often temporary.

- Mobilization therapy of the coccyx is relatively unfamiliar but is experienced as effective in clinical practice.

- Early recognition and targeted referral can prevent unnecessary diagnostic procedures and prolonged patient suffering.

Abstract

Coccydynia is an underrecognized condition in both medical practice and (para)medical education. Patients often present with long-standing symptoms that lead to significant functional impairment. In most cases, the diagnosis can be made quickly and clinically, based on localized pain over the coccyx, tenderness on palpation, and pain provoked by sitting. Imaging studies rarely contribute additional diagnostic value.

The treatment strategies primarily focus on pain reduction through injections, which often provide only temporary relief, or, in rare cases, surgical intervention. Also mobilizing therapy of the coccyx, typically delivered by physiotherapists, lacks robust scientific evidence, but is nevertheless frequently reported as effective in clinical practice.

This article discusses key diagnostic considerations for physicians and outlines the role and reported effectiveness of various treatment options, including mobilization therapy.

Improving knowledge of coccydynia can contribute to more targeted care and a reduction in long-term symptoms.

Case Report

A 36-year-old woman visits her physician exhausted and distressed. It is by now three years after childbirth, and she continues to experience severe pain in the coccygeal region and her reported functioning is at only 30% of her pre-pregnancy level. Following a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) related to the complicated delivery (treated with EMDR therapy) and management of local scar-related complaints through care by a gynaecologist, pelvic physiotherapist, and pain clinic, these symptoms improved, while the coccydynia progressively worsened. The orthomanual physician was unable to alleviate her symptoms and advised referral to the general practitioner for pain management. The general practitioner concluded that coccydynia could not be adequately treated at the pain clinic and referred her to a rehabilitation center. Due to the development of low back pain with neurological symptoms in the legs, she was send to a neurologist and an ultrasound examination of the coccyx led to a diagnosis of sacrococcygeal periarthritis. Both the neurologist and a gynaecologist consulted for a second opinion in Belgium advised referral to a pain clinic.

After two local corticosteroid injections failed to provide relief, she was back at the general practitioner again. He concluded, just like the previously consulted physicians and the pelvic physiotherapist, that no further treatment options were available.

After conducting her own online research, the patient found a specialized physiotherapist and wrote: “Every physician I have encountered seems unfamiliar with this condition, to whom can I still turn?” During the first consultation an arthrogenic dysfunction was identified and following this treatment, her symptoms were reduced by half within a few days. She also reported that, for the first time, she received clear answers to the questions she had asked all the healthcare providers before and had a logical explanation for her symptoms.

After five treatment sessions, her complaints had completely resolved.

This case illustrates several recurring features observed in the practice of specialized (physio)therapists. Patients often present with long-standing coccygeal pain associated with substantial functional limitations, have consulted multiple healthcare professionals without meaningful improvement, are frequently informed that their condition is not treatable, and ultimately find a specialized therapist through their own research.

This article aims to provide insight into the specific diagnostic features of coccydynia and to present an overview of treatment options described in the literature, along with their reported effectiveness.

Introduction

Coccydynia, pain localised at the coccyx, is a relatively rare condition that is often accompanied by high pain scores and substantial functional limitations in daily activities. That physicians and therapists are mostly unfamiliar with it, is explainable because the coccyx remains an underrecognised structure in many medical and paramedical training programs, even in the proctology and pelvic-floor physiotherapy curricula

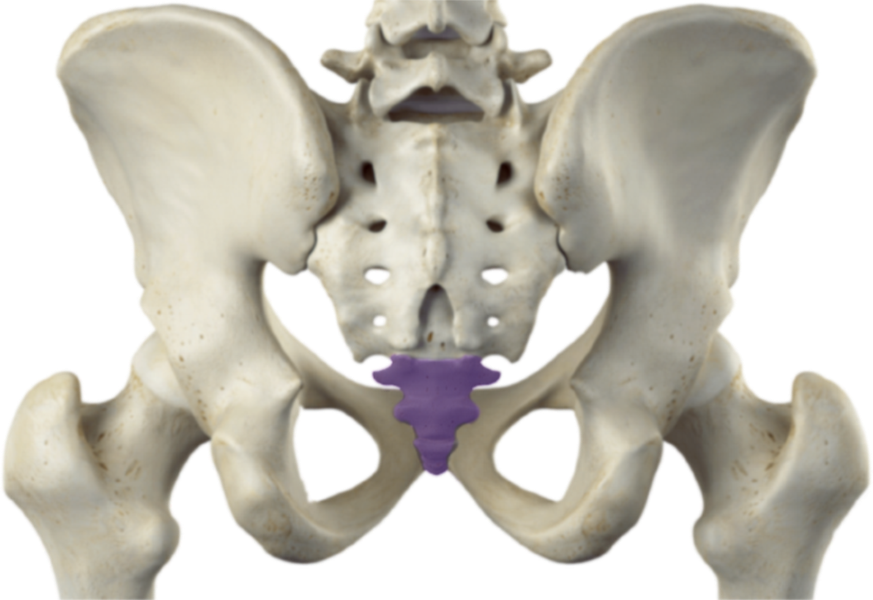

This last part of the spine consists of three to five vertebrae, which are typically fused into two to four segments that have intersegmental mobility 1–4. The commonly used terms tailbone or os coccygis misleadingly suggest, similar to the sacrum, that it is one single bone. The literature describes strong interindividual variation in the length, shape, and anatomical configuration of the coccyx.

Functional mobility occurs primarily in flexion–extension during sitting, rising from a seated position, and pelvic-floor muscle activation. Mobility of the coccyx is also required during childbirth.

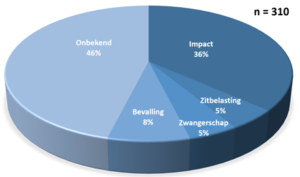

Symptoms may arise following a fall or childbirth, with prolonged sitting, or during pregnancy, although many cases are idiopathic. Structural lesions such as tumors or cysts are rare 5–7. Also fractures are uncommon 8, although arthrogenic luxtions or dispositions visible on imaging studies are frequently misinterpreted as fractures.

An underrecognized condition

Although there have been mentions of coccydynia in the literature for centuries 9, scientific research is limited and there is no widely supported guidelines for diagnostics and treatment 10. Coccydynia also doesn’t belong to a specific medical or paramedical discipline, although within diverse disciplines specialist emerged. That coccydynia is barely mentioned in in medical and paramedical educations, it is frequently under- or misdiagnosed by physicians and therapists. Radiologist Dr. A. Sukun that was active

as a physician on multiple continents, stated 11: “Patients often report that there is no specific diagnosis and that clinicians do not attach much importance to this condition.”

The general practitioner that is consulted first in cases of persistent and not understood health problems had an important role in diagnosing and informing the patient about the treatment options. Although they are available, the patient, just as at other healthcare professionals, often are informed there is little or nothing to be done about these problems if there is a referral, it is mostly for pain management.

Coccydynia in the Literature

according to Maigne

Coccygeal pain has already been described by physicians for centuries 9. Systematic research started since the 1980s and 1990s, high-quality studies remain scarce though 10. Both the number of published studies and the size of study populations are generally limited. Although reliable prevalence data are lacking, coccydynia is likely substantially underreported, leaving it a relatively small and underrecognized patient group. This results in little attention in the academic world and little knowledge by physicians and therapists. Therefore patients remain insufficiently treated, which is unnecessary, as this article will demonstrate.

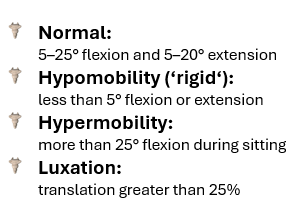

While coccydynia typically presents as posture- and movement-dependent pain, early investiga-tions attributed symptoms primarily to anatomical alignment of the coccyx 1. With the introduction of dynamic radiographic techniques by Dr. Maigne in the early 1990s, attention shifted toward biome-chanical etiology. Based on this pioneering work, Maigne et al. defined four categories of coccygeal mobility that are still being referred to these days: normal, hypomobile, hypermobile, and unstable 12–14. Of these only the latter two categories were considered pathological and clinically relevant 15.

Diagnostics

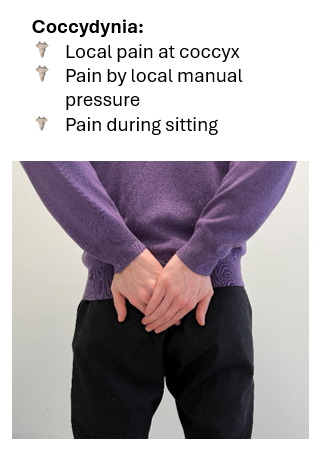

Coccdynia presents itself almost always as a sharp and local pain just behind the anus and at the coccyx, that is induced by local pressure or sitting. If one of these signs is absent, the diagnosis is less probable. The diagnosis can mostly be determined clinically. Pain is also possible in the area around the coccyx as well as pelvic dysfunction.

Through the years there seems to be consensus that coccydynia is mostly the result of mecha-nical dysfuntion in the coccygeal joints 12,13,15,16. Structural abnormalities like fractures and tu-mours are rare and other clinical indications often absent. In the literature only the exostosis is mentioned as a possible anatomical pain-inducing factor. This small bony outgrowth at the dorsal side of the tip of the coccyx is repor-ted only in 15% of the patients and is also pre- sent in 10–54% of asymptomatic individuals 2–4,17. These factors and the substantial anatomical variability in the coccygeal region, are the rea-son that not referring for imaging is justified and prevents unnecessary diagnostics and medicalisation. Unless there are indications for red flags, like severe recent trauma, unexplained weight loss, nocturnal pain, or neurological deficits, static imaging adds no valueand evaluation can be limited to the identifycation of local or regional coccygeal pain, provoked by manual pressure and sitting.

The following step will be a referral to a specialized clinician for local biomechanical assessment.

Medical Interventions

The findings and conclusions of mainly the studies by studies van Dr. Maigne et al., have formed the basis for the diagnosis and treatment of coccydynia. Because instability due to hypermobility or luxation cannot be directly corrected, the treatment has focused over the years on pharmacological and surgical interventions. These are mainly local corticosteroid injections to reduce pain and inflammation, anesthetic injections to temporarily block nerve conduction, and coccygectomy, the only surgical option and that consists of partial or complete removal of the coccyx. Although patients experience relief from these interventions, clinical outcomes remain variable.

The expert opinion is that the efficacy of injections for coccydynia depends strongly on the physician’s expertise, particularly in identifying the optimal site of infiltration and ensuring precise delivery. Symptom improvement after injection is generally short-lived, consistent with findings of these same injections for other musculoskeletal disorders 18–20. One of the few studies that looked at long-term follow-up reported that only 15% of patients experienced sustained improvement after three years 21. Physicians specializing in injection therapy for coccydynia observe that pain relief often outlasts the pharmacological duration of the drug and that recurrent pain is usually less severe than before the injection 16. This effect has been attributed to a “reset” of pain-processing and -regulating pathways in the nervous system 16. Reliable data on the proportion of patients achieving permanent or long-term improvement are scarce. Dr. Maigne reported that among more than 500 patients treated with anti-inflammatory injections, 60–70% showed improvement within the first two to four months, but only about 30% were pain-free after one year 22.

The outcomes of coccygectomy have likewise been investigated mainly in small patient cohorts and focusing primarily on short-term results. Several studies describe a substantial improvement, varying between 70–85% reduction in pain, but few provide data on the long-term durability of these effects. Dr. Foye noted that although most patients experience a significant decrease in symptoms after coccygectomy, fewer than 10% achieve complete pain relief 16. The procedure itself is also highly invasive, involving removal of a central pelvic structure with key attachments of the pelvic floor muscles and the rehabilitation period is normally four to eight months 23. Also the risk of complications, particularly postoperative wound infections, is considerable. Consequently, there is broad consensus among both surgeons and non-surgeons that coccygectomy should be considered only as a last resort, and only when conservative measures fail 16,24. Finally not all patients are eligible for surgery, as strict exclusion criteria are typically applied to minimize surgical risk and optimize outcomes.

For the effectiveness of both interventions the available studies are scarce, the research groups small and methodological quality limited 10.

Manual Mobilizations

The first documented treatments for coccydynia involved manual mobilization of the coccyx 9. Initially, this was performed exclusively via an internal approach, using a finger intra-rectal, where the coccyx was typically mobilized in a dorsal direction. Over the centuries, this method was almost consistently reported as effective by physicians 9,25,26 and later also by therapists from various disciplines 27–33.

Enthusiasm for the clinical effectiveness of mobilizing interventions continues to be reported today, both by physicians and therapists and by patients, for example in online patient reviews 34–36. Within the medical community, even among experts in coccydynia, this approach receives little attention. This is likely due to prevailing assumptions regarding the condition. Next to that hypomobility is generally not considered clinically relevant 13,16, instability even is assumed to be the underlying cause in approximately half of cases 13,16. This is flowed by anatomical variations such as exostosis or chronic inflammation. For all the conditions above, mobilization is not a logical treatment option.

The two most widely cited studies on mobilizing interventions for the coccyx, assessed their effectiveness as low to moderate. These studies 37,38, conducted by physicians who themselves rarely apply these techniques in practice, included relatively small cohorts (74 and 50 patients). Most striking was that the treatment dose was limited to only several minutes and only three sessions. Nevertheless, approximately 25% of patients receiving three sessions of 5 minutes reported an improvement of 60% or more. This improvement was still present six months afterwards 38. Similarly, among patients receiving only three sessions of 1.5 minutes, about 25% reported 60% or more improvement, which even remained evident even two years post-intervention 37. Statistically, however, these effects were deemed non-significant, moderate and poor and did not prompt further investigation. Nevertheless, there is a clear indication of effectiveness of a very minimal treatment dose and that this leads to lasting results, which can be explained from the aim to treat an underlying cause and not just the symptom. Despite the signals of efficacy these studies didn’t result in additional research and up to the present day, just as for the other interventions for coccydynia, robust scientific studies on this treatment remain lacking 10.

In clinical practice, therapeutic mobilization has therefore become marginalized, and coccydynia patients are seen almost exclusively by physicians. From a limited knowledge base and biomechanical perspective, mobilization is seldom considered as a treatment option, and patients are instead mainly directed toward treatment of the symptoms or surgical resection of the nociceptive source. This alongside a significant development of mobilization of the coccygeal joints in the past ten to fifteen years.

The work of the Dutch manual therapist Meine Veldman, who developed an external treatment method that does not require rectal examination, has led to a further increase in successfully treated patients with coccydynia.

treatment trajectories

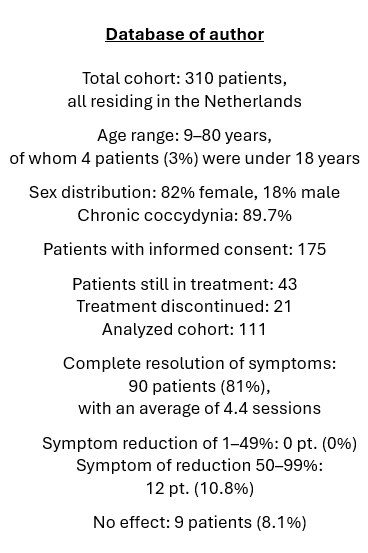

The clinical results of this low-intensity, cost-effective, and causally oriented approach are not less than those of medical interventions. According to the author’s clinical database, who is specialised in the external mobilization treatment of coccydynia, approximately 80% of patients become completely symptom-free within often only a few sessions.

These results are consistent with clinical observations reported over the centuries, as well as with the practical experiences

of colleagues who also apply mobilizing techniques in the treatment of coccydynia. Apart from a small number of academic theses, two physiotherapy master’s and four bachelor’s theses from the Health Sciences program at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, there are currently no high-quality studies supporting these findings. British chiropractor Michael Durtnall has reported comparable clinical outcomes of arthrogenic mobilization techniques, sup-ported by imaging studies, at inter-national conferences on coccydynia and lumbago 39,40. Unfortunately, these data have never been published in journals. Scientific studies of the results from the author’s clinical database are currently, in collaboration with Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, being prepared.

Improving Care for Coccydynia Patients

With this article, the author aims to contribute to closing the knowledge gap regarding coccydynia among physicians. Coccygeal pain is in most cases easily diagnosable and very well treatable through targeted mobilization therapy or via medical interventions, two approaches that are very complementary. The author calls for higher-quality research into the effectiveness of treatments for this niche condition so there will also be scientific acknowledgement. The field of research is still in its infancy, particularly with respect to mobilizing interventions. Nevertheless, care for patients with coccydynia could be significantly improved by broadening the prevailing paradigm and ensuring that therapeutic interventions aimed at improving coccygeal mobility are better know by (primary care) physicians and more often presented as a treatment option to patients. At present, many patients only find specialized therapists through their own online searches.

Further development of knowledge can significantly reduce the amount of patients that leave their physician’s office feeling misunderstood and untreated. The low threshold and effective mobilization therapy can then help even more patients with a solution for their often chronic pain and functional limitations.

Further information for both patients and physicians about coccydynia, as well

as a directory of specialized therapists, can be found at this website:

www.tailbonetherapist.com

Practical clinical lessons

- Coccydynia is mostly clinically diagnosable with local pain, tenderness with manual pressure at the coccyx and pain while sitting.

- Routine imaging provides for coccydynia usually little added value and is only indicated in the presence of specific red flags.

- Medical interventions are often aimed on symptoms and offer often no lasting relief and surgery is a last resort.

- Mobilization therapy of the coccyx is relatively unfamiliar and is for centuries linked to clinical effectiveness.

- Targeted referral and clear information for patients can prevent long term suffering and unnecessary healthcare procedures.

References

1. Postacchini, F. & Massobrio, M. Idiopathic coccygodynia. Analysis of fifty-one operative cases and a radiographic study of the normal coccyx. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery – Series A 65, (1983).

2. Woon, J. T. K., Perumal, V., Maigne, J. Y. & Stringer, M. D. CT morphology and morphometry of the normal adult coccyx. European Spine Journal 22, (2013).

3. Marwan, Y. A. et al. Computed tomography-based morphologic and morphometric features of the coccyx among arab adults. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 39, (2014).

4. Shams, A., Gamal, O. & Mesregah, M. K. Sacrococcygeal Morphologic and Morphometric Risk Factors for Idiopathic Coccydynia: A Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Global Spine J 13, (2023).

5. Karadimas, E. J., Trypsiannis, G. & Giannoudis, P. V. Surgical treatment of coccygodynia: An analytic review of the literature. European Spine Journal vol. 20 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-010-1617-1 (2011).

6. Woon, J. T. K. & Stringer, M. D. Clinical anatomy of the coccyx: A systematic review. Clinical Anatomy vol. 25 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.21216 (2012).

7. Tzerefos, C. et al. Bursitis of the coccyx in an adult with rheumatoid arthritis mimicking a sacrococcygeal meningocele. Surg Neurol Int 12, (2021).

8. Maigne, J. Y., Doursounian, L. & Jacquot, F. Classification of fractures of the coccyx from a series of 104 patients. European Spine Journal 29, (2020).

9. Miles, J. A history of coccydynia. in First International Symposium on Coccyx Disorders 8–14 (2016).

10. Andersen, G. et al. Coccydynia—The Efficacy of Available Treatment Options: A Systematic Review. Global Spine Journal vol. 12 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1177/21925682211065389 (2022).

11. Sukun, A., Cankurtaran, T., Agildere, M. & Weber, M. A. Imaging findings and treatment in coccydynia – Update of the recent study findings. RoFo Fortschritte auf dem Gebiet der Rontgenstrahlen und der Bildgebenden Verfahren vol. 196 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1055/a-2185-8585 (2024).

12. Maigne, J. Y., Guedj, S. & Straus, C. Idiopathic coccygodynia: Lateral roentgenograms in the sitting position and coccygeal discography. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 19, (1994).

13. Maigne, J. Y., Doursounian, L. & Chatellier, G. Causes and mechanisms of common coccydynia: Role of body mass index and coccygeal trauma. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 25, (2000).

14. Maigne, J. Y. & Tamalet, B. Standardized radiologic protocol for the study of common coccygodyma and characteristics of the lesions observed in the sitting position: Clinical elements differentiating luxation, hypermobility, and normal mobility. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 21, (1996).

15. Maigne, J. Y., Pigeau, I. & Roger, B. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in the painful adult coccyx. European Spine Journal 21, (2012).

16. Foye, P. Tailbone Pain Relief Now! . (Top Quality Publishing, 2015).

17. Woon, J. T. K., Maigne, J. Y., Perumal, V. & Stringer, M. D. Magnetic resonance imaging morphology and morphometry of the coccyx in coccydynia. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 38, (2013).

18. Coombes, B. K., Bisset, L. & Vicenzino, B. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroid injections and other injections for management of tendinopathy: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. The Lancet 376, (2010).

19. Stone, S., Malanga, G. A. & Capella, T. Corticosteroids: Review of the history, the effectiveness, and adverse effects in the treatment of joint pain. Pain Physician 24, (2021).

20. Kamel, S. I., Rosas, H. G. & Gorbachova, T. Local and Systemic Side Effects of Corticosteroid Injections for Musculoskeletal Indications. American Journal of Roentgenology vol. 222 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.23.30458 (2024).

21. Finsen, V., Kalstad, A. M. & Knobloch, R. G. Corticosteroid injection for coccydynia a review of 241 patients. Bone Jt Open 1, (2020).

22. Maigne, J. Y. Treatment of coccydynia. https://www.coccyx.org/treatmen/maigneco.htm (2000).

23. Maigne, J. Y., Lagauche, D. & Doursounian, L. Instability of the coccyx in coccydynia. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery – Series B 82, (2000).

24. Sandrasegaram, N., Gupta, R. & Baloch, M. Diagnosis and management of sacrococcygeal pain. BJA Education vol. 20 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2019.11.004 (2020).

25. Yeomans, F. C. Coccygodynia – a new method of treatment by injections of alcohol. Medical Record (1866-1922) 86, 322 (1914).

26. Oakman, C. S. Traumatic Luxation of the Coccyx. Radiology 17, (1931).

27. Khatri SM Nitsure P., J. R. S. Effectiveness of coccygeal manipulation in coccydynia: A randomized control trial. Indian J Physiother Occup Ther 4, (2010).

28. Marinko, L. N. & Pecci, M. Clinical decision making for the evaluation and management of coccydynia: 2 case reports. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy 44, (2014).

29. St. Claire, S. Rationale and approach to internal coccyx adjustments. Journal of the American Chiropractic Association (2003).

30. Liram, A. & Davidson, E. Treatment of coccydynia by chiropractic manipulation per rectum under local anaesthesia: A multiple-case study. Pain Relief Unit, Hadassah University Medical Centre, Jerusalem.

31. Origo, D., Tarantino, A. G., Nonis, A. & Vismara, L. Osteopathic manipulative treatment in chronic coccydynia: A case series. J Bodyw Mov Ther 22, (2018).

32. Alexandre, K. & Channell, M. K. Osteopathic approach to the treatment of a patient with an atypical presentation of coccydynia. Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 119, (2019).

33. Galhom, A., Al-Shatouri, M. & El-Fadl, S. A. Evaluation and management of chronic coccygodynia: Fluoroscopic guided injection, local injection, conservative therapy and surgery in non-oncological pain. Egyptian Journal of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine 46, (2015).

34. Zorgaart Nederland, therapeut R. H. C. W. Zorgkaart Nederland. https://www.zorgkaartnederland.nl/zorgverlener/fysiotherapeut-wilbers-r-h-c-294713.

35. R. Wilbers. The Tailbone Podcast: Expert Talks. https://destuittherapeut.nl/podcast/.

36. Miles, J. Patient reports of coccydynia treatment effectiveness. in Second International Symposium on Coccyx Disorders (2018).

37. Maigne, J. Y. & Chatellier, G. Comparison of three manual coccydynia treatments: a pilot study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 26, (2001).

38. Maigne, J. Y., Chatellier, G., Faou, M. Le & Archambeau, M. The treatment of chronic coccydynia with intrarectal manipulation: A randomized controlled study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 31, (2006).

39. Durtnall, M. Manual therapy for coccyx pain. in First International Symposium on Coccyx Disorders 117–128 (Paris, 2018).

40. Durtnall, M. Coccyx Manipulation Statistics. in 8th International Congress of Back Pain and Pelvic Pain (Dubai, 2013).